I began the journey I’ve been documenting here in an attempt to unravel the history of an ancient war. The heart of that history is a poem. What this impressed upon me is that if the pen is mightier than the sword, poetry is more powerful than an army. That presented an imperative question: what is poetry for? I’ve thought long and hard about that, venturing into realms I had never been before, and I think I found an answer, so I’ll share it for what it may be worth. Keep reading…

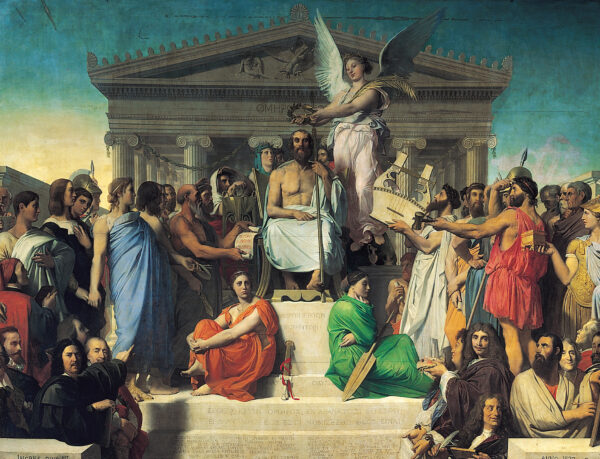

The Uniqueness of Homer.

One of the joys of doing what I’m doing is being “stung by the splendor of a sudden thought.”1 This happened while I was working on my roadmap for the Trojan War legend and while there are hints of it in my essay, True Colors, it was nascent and did not emerge until later. I’ve been thinking of it ever since and decided I’d record my thoughts and post them before moving on. If I’m all wet, perhaps some knowledgeable person can correct me.

The thought is this: Homer seems truly unique to me. Now I can imagine that garnering the response, “Well, duh,” since it hardly seems to be revelatory on its face, so I’ll try to explain. Keep reading…

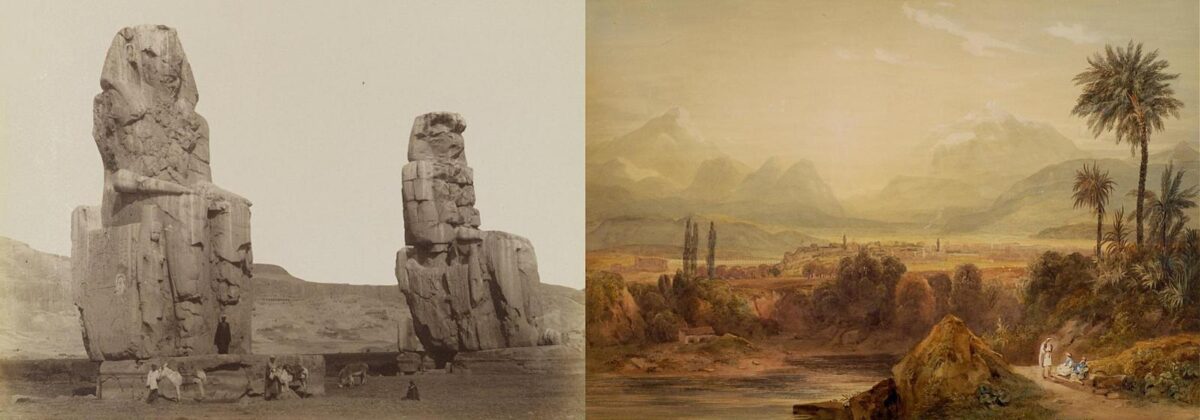

A Tale of Two Cities: Mistaken identity or sour grapes?

In our version of the Iliad, there is a mention of “Egyptian” Thebes. In Wrestling with Proteus, I commented in a footnote that this must be an interpolation because in context, Boeotian Thebes is clearly meant. I then remarked how the text came to say Egyptian Thebes was a topic for another essay. This is that essay. Keep reading…

A Voyage to Nowhere? The Teuthranian Debacle.

The Teuthranian Expedition, referred to by Martin West as the “Teuthranian Debacle” is an important, but odd, episode in the overall Trojan War legend. This essay briefly reviews the purpose of the episode and two suggestions for its origin, reflecting how analyst’s backgrounds direct our interpretations of literature. Keep reading…

Our Iliad is not Homer’s Iliad: An exercise in “original intent.”

It is acknowledged that Homer’s Iliad has been subjected to editorial revision during its long history, some of which appear to have occurred early on. These revisions are distinct from the questions of multiformity imposed by its predominantly oral dissemination. In this essay, I will examine three of the most significant, and probably earliest, revisions (technically referred to as interpolations) in regards to how they may have changed, and possibly obscured, the original intent of Homer’s Iliad. Keep reading…

Dio or Don’t You?

Another short interlude while I get some more ducks in a row. Keep reading…

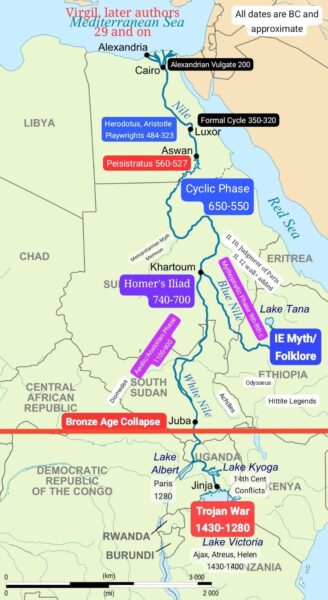

The Geography of a Legend: The Cyclic Phase and Final Phase.

In this final part of my proposed roadmap to the evolution of the Trojan War legend, I discuss the Cyclic phase, which occurred from about the mid-7th century to the mid-6th century, amalgamating Homer’s Iliad with the Mythopoetic poems into one tradition. Thereafter, the stories of the Trojan War became assembled into “cycle,” first in Athens under Peisistratus or his son, between 560 and 527, and finally, in a formal sense, during Aristotle’s day, around 350-320. This post-Cyclic period (roughly 520-300) saw another great creative outburst related to the Trojan War; art, plays and poetry. Much of the surviving material about the legend dates from this period. Keep reading…

The Geography of a Legend: Aeolic/Anatolian Phase, the Mythopoetic Phase and Homer

In Part 2 of my proposed roadmap to the development of the Trojan War legend, I cover the Aeolic/Anatolian phase, which occurred in mainly in western Anatolian in the early Iron Age, and Mythopoetic phase, which happened along with the flowering of Ionian poetry in the 8th century, but may have had roots going back into the 9th. These are the two traditions with which Homer worked in the latter part of the 8th century, and whom I touch on only briefly, as I will cover his epic separately. Keep reading…

The Geography of a Legend: A roadmap to history’s most misunderstood conflict.

Gregory Nagy formalized his theory of how epics develop in his evolutionary model (I provided a brief synopsis of it in my essay, Homer and the Written Word), and Jonathan Burgess offered up an “arboreal” simile when he said if the Trojan War legend were a tree, the Iliad and Odyssey would be “a couple of small branches” while the Cyclic poems would be “somewhere in the trunk.” (The Cyclic poems are the six lost works that complete the legend.) Inspired by them, I came up with a “hydraulic” model for the legend’s evolution, based on the idea of rivers and deltas, which I’m introducing here. Keep reading…

Analytical Target Fixation. A short interlude while I get some ducks in a row…

A short interlude while I get some ducks in a row… Keep reading…